The Real Challenge in FE and PE Exam Prep

- The FE exam covers several subjects—and the PE includes even more. It’s a massive undertaking, with so much material that by the time students study their final topics, they’ve already forgotten much of what they studied at the start.

- But the real challenge isn’t just the volume of study materials—it’s the way students learn.

- They rely on passive study methods like rereading and highlighting which may feel productive, but they don’t create lasting understanding.

- Research shows that without active retrieval, knowledge fades quickly.

- To succeed, students need more than effort—they need a smarter approach.

Progressive Exams (Assessment‑as‑Learning)

Progressive exams—also called assessment as learning—turn testing into an instructional tool rather than a mere end‑of‑course checkpoint. Decades of cognitive‑science and education research identify six core reasons this approach outperforms the traditional “teach‑then‑one‑big‑test” model:

| Why it works? | What happens in the brain? |

|---|---|

| Retrieval practice ("testing effect") | Every mini-exam forces students to pull information from memory, strengthening neural connections and dramatically improving long-term retention compared with re-reading or highlighting. |

| Spaced repetition | Successive exams are naturally spread over weeks, giving the brain time to forget a little and then relearn—optimal for durable memory. |

| Immediate, formative feedback | Results arrive while the material is still fresh, pinpointing misconceptions before they fossilize and guiding targeted review. |

| Metacognitive skill-building | Students compare scores across exams, reflect on strategies, and adjust—a habit of self-regulation essential for lifelong learning. |

| Motivation & sustained effort | Regular low-stakes checkpoints break large goals into attainable steps, keeping engagement high and reducing last-minute cramming stress. |

| Reduced high-stakes anxiety | Familiarity with exam conditions through repeated practice lowers test anxiety and boosts confidence for the final, official assessment. |

Most people believe that the more you study, the more you’ll remember. But what if that’s not true?

Research and several experimental studies have shown that it is not the case.

The Hidden Power of Testing

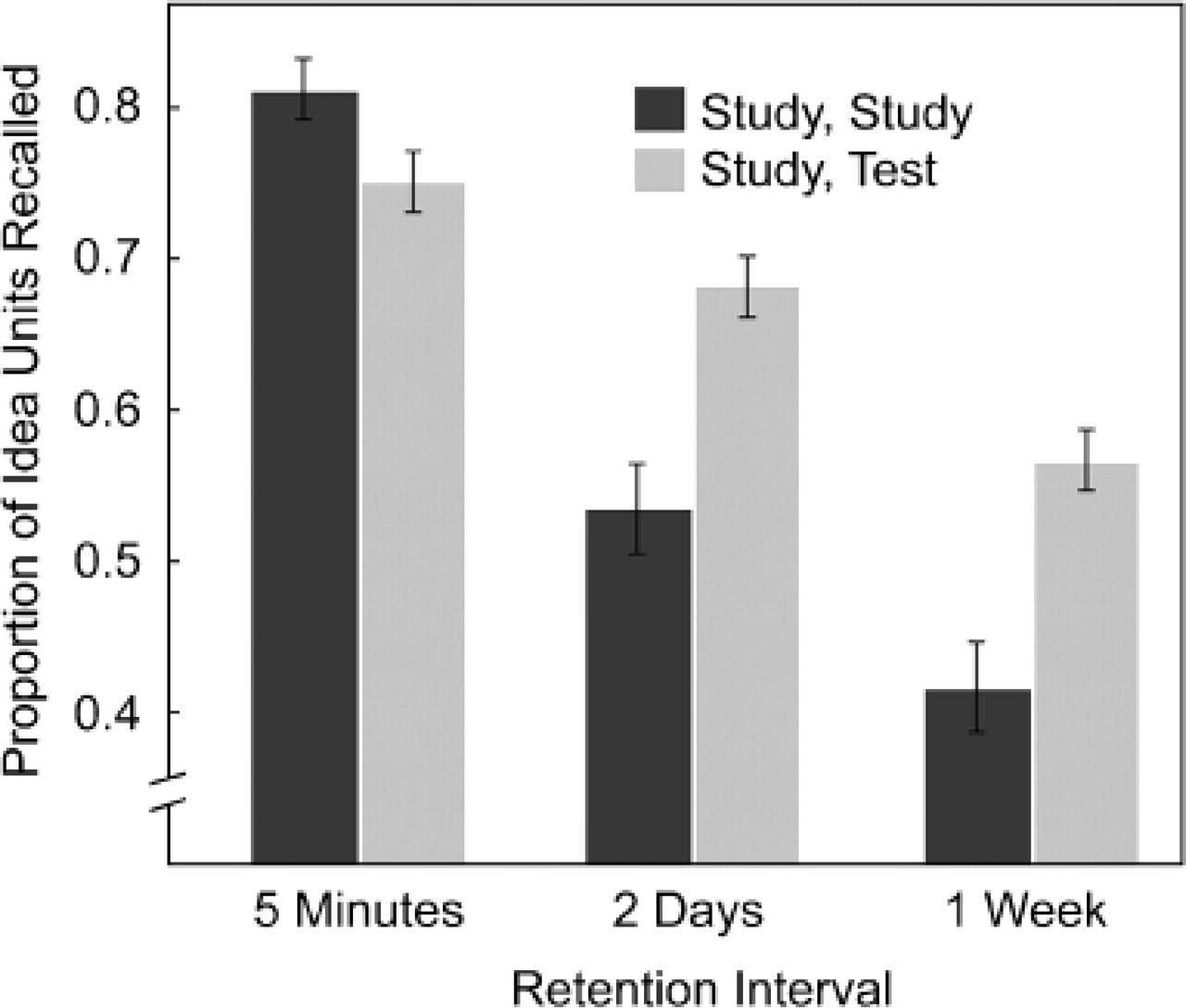

In an experimental study, 120 students were given scientific passages and tested after 5 minutes, 2 days, and 1 week. These students were divided into following two groups to compare their performance.

Group 1 (Restudy Group)

- Read the passages twice (Study, Study)

Group 2 (Study + Test Group)

- Read the same passages once and then took a practice test (Study, Test)

Repeated Study Vs Repeated Test

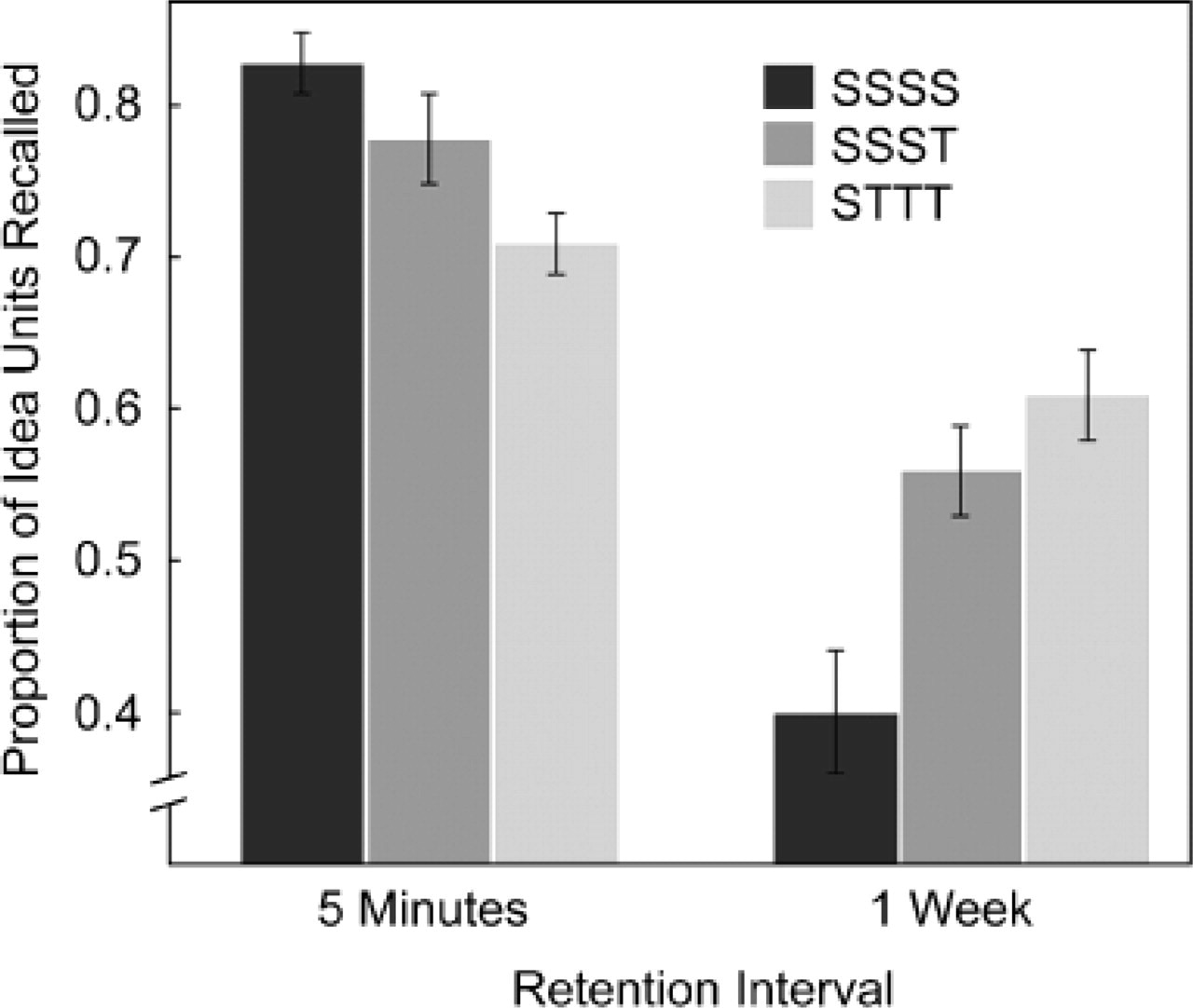

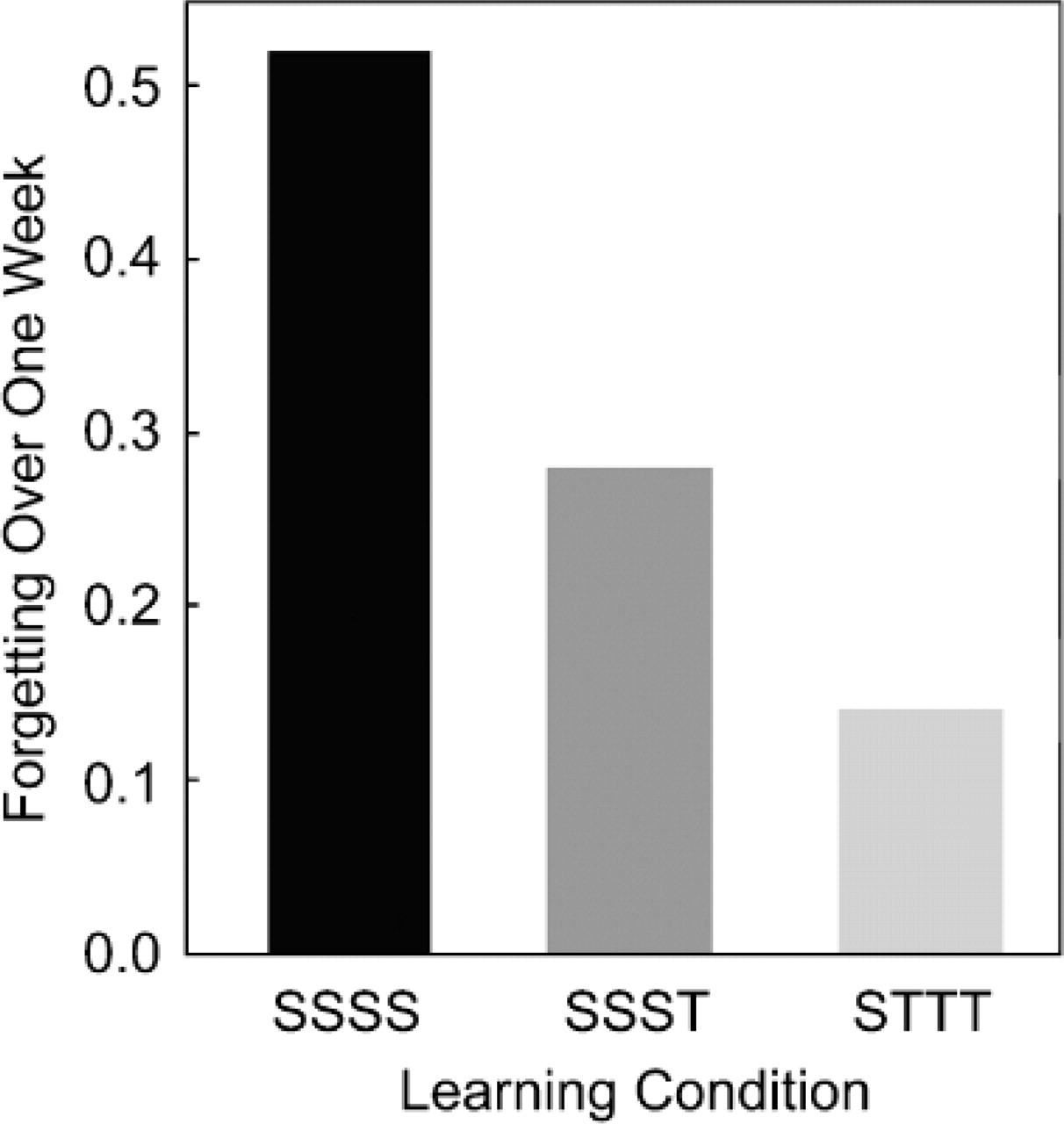

In another experimental study, 180 students were given scientific passages and tested after 5 minutes, and 1 week. These students were divided into following three groups to compare their performance.

Group 1 (Repeated Study Group)

- Read the passages 4 times (SSSS)

Group 2 (Repeated Study + 1 Test Group).

- Read the same passages 3 times and then took 1 practice test (SSST)

Group 3 (Study Once + Repeated Test Group)

- Read the same passages once and then took 3 practice test (STTT)

Key Takeaways

Testing improves long-term retention more than repeated study.

The testing effect emerges more clearly over time, not immediately.

Despite poor performance, students in the SSSS (repeated study) group believed they would remember more than the testing groups—showing a metacognitive illusion.

Practical Implications

These experiments provide strong evidence that retrieval practice (testing) is more effective than repeated studying for long-term retention.

This has clear implications for study habits: regular, spaced testing is one of the most efficient ways to promote durable learning.

Testing should be viewed not just as assessment, but as a learning tool.

Regular, low-stakes recall testing specially with feedback significantly boosts long-term memory.

Testing prevents forgetting better than passive review—even with less study time.

Students often misjudge their learning—favoring study over testing even when it's less effective.

What Makes Our Program Different

- Progressive, step-by-step exam prep built around a strategic study plan.

- Realistic exam simulations

- Personalized performance feedback

- Guidance from experts

Why our programs work?

- Repetition + Gradual Scope Expansion = Long-Term Retention

- Build mastery step-by-step — not all at once

- Train your timing, focus, and test-taking strategy

- Testing strengthens memory through retrieval.

- Retrieving knowledge makes it stick better than just reviewing.

- Testing isn’t just for measuring learning—it creates learning.

- Testing transforms forgetting into remembering.

- If you want knowledge to last, don’t just study more—start retrieving it.

Enroll now and follow the plan that ensures you’re ready.